Classroom Games for Teaching Economics

Ready to play, Nothing to install, No need to register!

Students play online on their phones, tablets or laptops.

14 simulations to play alone:

48 multiplayer games:

If you are a player:

If you are an instructor:

2D Hotelling Pricing Game Top 5! oTree

Players are managers of a firm that compete with three other firms to sell a product to the customers of a square country.

2D Hotelling Complete (Pricing and Location) Game oTree

This is the complete variant of the game above.

Price discrimination, vertical differentiation and peak-load pricing Top 5!

Players take price and quantity decisions for an airline on a given route against a robot competitor. Illustrates notions such as marginal cost/average cost, variable cost/fixed cost, sunk cost, short-run/long-run cost, price discrimination (yield management), elasticity of demand, peak-load pricing.

Warning From lessons learned in recent years, we would recommend that students play the single-player mode of this simulation (located at the top of this page, in the simulations list) rather than this version. It gives them the flexibility to revisit decisions and learn through trial and error, as opposed to being restricted by a shared game's tempo. However, we will still maintain the multiplayer version for instructors who are accustomed to it and might prefer it, based on their experience and judgement.

Stackelberg Game

Each player repeatedly plays two Stackelberg games against the same competitors. Once as a first mover, once as a follower. 2 players on each market and P=20-(Q1+Q2).

Cournot Game

Each player repeatedly plays two cournot games against the same competitors. 2 players on each market and P=20-(Q1+Q2). Preferably, play after the Stackelberg game, so that players get used to the reaction functions.

Bertrand Competition oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant. Each of them represents a firm and sets a price, anything from 0 to 100 points. A buyer in the market buys one unit of the product at the lower price.

When do first-movers have an advantage? A Stackelberg classroom experiment - Cournot (R. Rebelein & E. Turkay) oTree

"The timing of moves can dramatically affect firm profits and market outcomes. When firms choose output quantities, there is a first-mover advantage, and when firms choose prices, there is a second-mover advantage.

When do first-movers have an advantage? A Stackelberg classroom experiment - Bertrand (R. Rebelein & E. Turkay) oTree

This is the Bertrand variant of the game presented above.

Patents and R&D: A Classroom Experiment (A. Diduch) oTree

"... This classroom experiment provides students with an introduction to two competing models of the impact of patents on R&D: the ‘winner-take-all’ model contains incentives for excessive research effort and the ‘knowledge spillover’model contains incentives for free riding.

Can Contracts Solve the Hold-Up Problem? (E. Hoppe and P. Schmitz) Top 10! oTree

"How to induce trading partners to make relationship-specific investments is a central theme in the contract-theoretic literature. A party may have insufficient incentives to make non-contractible investments if it fears that it will be held up by its partner in the future.

The Trading Pit Market Experiment oTree

This experiment is used to introduce students to the working of competitive market.

Duopoly with Differentiated Demand and Capacity Constraints (B. Çelen & S. Feldmann) oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant, and play 6 rounds of an airline duopoly game with capacity constraints and differentiated demand.

The Beer Game (J. Sterman) oTree

"The purpose of the game is to understand the distribution side dynamics of a multi-echelon supply chain used to distribute a single item, in this case, cases of beer." The Beer Game, by John Sterman .

The 5 market games below can be played on their own or one after the other:

In those games, to allow comparisons, demand on a market is calibrated to be proportional to the number of firms that can be active on it. For example, demand on a market with 6 firms will be 50% more important than on a market with 4 firms. Consequently, potential revenue by firm is the same in each market. (Reference demand data).

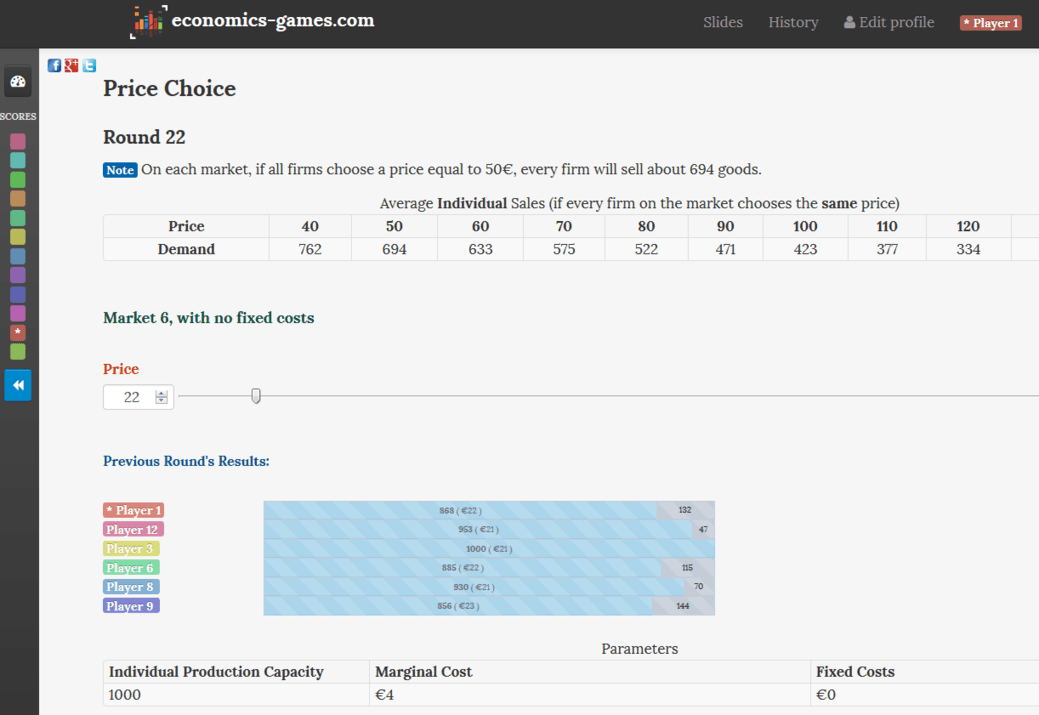

Competition Game: Impact of fixed costs and capacity constraints on price and profit, with differentiated goods Top 5!

Oligopolistic price competition for differentiated products. Players repeatedly compete on five different markets with only slight differences: with or without unavoidable fixed costs, with or without avoidable fixed costs, with low or high production capacities.

Warning From lessons learned in recent years, we would recommend that students play the single-player mode of this simulation (located at the top of this page, in the simulations list) rather than this version. It gives them the flexibility to revisit decisions and learn through trial and error, as opposed to being restricted by a shared game's tempo. However, we will still maintain the multiplayer version for instructors who are accustomed to it and might prefer it, based on their experience and judgement.

Introduction to the Competition Games: Sunk costs and monopoly

This is just an introductory variant of the game above, where players are monopolies on their markets and with only two markets (with or without sunk cost, both markets with the same capacity constraints). This is a good introduction to sunk costs and, if played in combination with the game above, it can also be useful to underline differences between monopoly and oligopoly (in these games, demand is proportional to the number of players).

Competition Game: Impact of fixed costs and capacity constraints on price and profit, with homogenous goods

This is the same game as the first competition game except that goods are now homogenous

Competition Game: Impact of the number of competitors on price and profit

Oligopolistic price competition for differentiated products. Players repeatedly compete on two different markets with a different number of competitors (demand is proportional to the number of competitors). Useful to study the impact of the number of firms on competition intensity.

Competition Game: Price and quantity competition and CO2 environmental policies (quotas, taxes and emission permits) Top 10!

Impact of environmental policies in a setting with quantity precommitment followed by price competition. Players repeatedly take price and quantity decisions on four markets subject to different environmental policies for CO2 emissions: no policy benchmark, unit taxes, quotas or permits. Demand is the same as in the other competition games (differentiated demand).

Warning From lessons learned in recent years, we would recommend that students play the single-player mode of this simulation (located at the top of this page, in the simulations list) rather than this version. It gives them the flexibility to revisit decisions and learn through trial and error, as opposed to being restricted by a shared game's tempo. However, we will still maintain the multiplayer version for instructors who are accustomed to it and might prefer it, based on their experience and judgement.

Voluntary contribution to a public good

Each player freely chooses its participation in financing of a pure public good. A player's payoff is equal to twice the average participation minus its individual participation. Repeated Game.

Tragedy of the commons (D. Hazlett) Top 10!

Players jointly own a renewable resource and must make harvesting decisions over a number of periods. This is the classic experiment created by Denise Hazlett ("A Common Property Experiment with a Renewable Resource." Economic Inquiry, 35, October 1997, pp. 858-861), also described in the great site, games economists play (game #75).

Competition Game: Price and quantity competition and CO2 environmental policies (quotas, taxes and emission permits) Top 10!

Impact of environmental policies in a setting with quantity precommitment followed by price competition. Players repeatedly take price and quantity decisions on four markets subject to different environmental policies for CO2 emissions: no policy benchmark, unit taxes, quotas or permits.

Warning From lessons learned in recent years, we would recommend that students play the single-player mode of this simulation (located at the top of this page, in the simulations list) rather than this version. It gives them the flexibility to revisit decisions and learn through trial and error, as opposed to being restricted by a shared game's tempo. However, we will still maintain the multiplayer version for instructors who are accustomed to it and might prefer it, based on their experience and judgement.

The Herd Immunity Game (A. Grant, J. Bruehler & A. Chiritescu) oTree

A particularly potent strain of the flu virus has been discovered in the class, but a vaccine exists. Receiving the vaccination is both painful and expensive for individuals. The more people get vaccinated, the less unvaccinated persons are likely to catch the flu.

Policies with Varying Costs and Benefits: A Land Conservation Classroom Game (S. Dissanayake & S. Jacobson) oTree

This game puts "students in the role of landowners who must decide whether to conserve land in different policy environments: flat conservation payments, agglomeration bonuses, and a conservation auction.

The Carbon Trading Game (R. Fouquet) oTree

"A simple game of the market for carbon dioxide tradable permits... As a pedagogical tool, this game benefits from simplicity ... and enables students to grasp the concepts and remember them through the intensity and fun of a trading 'pit'.

The Red/Green Simulation (J. Bruehler, A. Grant & L. Ghent) oTree

"Collective action problems are at the heart of many economic issues. Often, students have trouble comprehending how society ends up with a less than optimal outcome, and may incorrectly assume that someone must want the outcome that occurs. Correcting this error is made difficult by the biases that students bring to these issues.

Prisoner's Dilemma Top 10!

A repeated Prisoner's Dilemma game.

| Player 1 / Player 2 | Compete | Cooperate |

|---|---|---|

| Compete | 1 , 1 | 5 , -1 |

| Cooperate | -1 , 5 | 3 , 3 |

A n-player Chicken Game

For a project to succeed, a particularly painful task must be undertaken by at least one member of a team. Team members simultaneously choose whether or not to undertake the task. If players behave according to the symetric mixed-strategy nash equilibrium of the game, the more players in the team, the less often the project succeeds. Repeated Game.

Asymmetric Matching Pennies Game

A repeated Asymmetric Zero-Sum Game. A good introduction to Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibria.

| Player 1 / Player 2 | Heads | Tails |

|---|---|---|

| Heads | 5 , -5 | -1 , 1 |

| Tails | -9 , 9 | 5 , -5 |

Battle of the sexes

A standard battle of the sexes game, as described here. Repeated game.

| Player 1 / Player 2 | Prefered Option | Second Option |

|---|---|---|

| Prefered Option | 0 , 0 | 4 , 2 |

| Second Option | 2 , 4 | 0 , 0 |

Simultaneous Entry Game (repeated)

A repeated (simultaneous) Entry Game. Another introduction to Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibria.

| Player 1 / Player 2 | Stay Out | Enter |

|---|---|---|

| Stay Out | 0 , 0 | 0 , 100 |

| Enter | 100 , 0 | -50 , -50 |

The Beauty Contest oTree

Each player will be asked to pick a number between 0 and 100. The winner will be the participant whose number is closest to two-third of the average of all chosen numbers.

Ultimatum Game oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant (depending on your choice when you create the game, pairs will change each round or stay the same). The two participants in a pair will have two different roles: the proposer and the responder. Players will be assigned randomly to a role and will keep it until the end of the game.

Each pair of players will together receive 100 points. The experiment is about how to divide this amount. The proposer will make the responder a take-it-or-leave-it offer, which the responder can accept or reject. If the offer is rejected, both will receive 0 points.

Matching Pennies oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant, and play 10 rounds of "Matching Pennies".

| Player A / Player B | Heads | Tails |

|---|---|---|

| Heads | 0 , 100 | 100 , 0 |

| Tails | 100 , 0 | 0 , 100 |

The Traveler's Dilemma (K. Basu) oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant. Players from each pair are travelers who just returned from a remote island where both of them bought the same antiques. Unfortunately, the airline managed to smash the antiques. The airline manager assures them of adequate compensation. Without knowing the true value of your antiques, he offers players the following scheme.

The Trust Game oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant (depending on your choice when you create the game, pairs will change each round or stay the same). In each pair, one player will be selected at random to be participant A; the other will be participant B. They will keep this role until the end of the game.

To start, participant A receives 100 points, participant B receives nothing. Participant A can send some or all of his 100 points to participant B. Before B receives these points they will be tripled. Once B receives the tripled points he can decide to send some or all of his points to A.

The Bargaining Game oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant. In each pair, there are 100 points for players to divide. They have to simultaneously and independently demand a portion of the 100 points for themselves.

If the sum of demands is smaller or equal to 100 points, both players get what they demanded. If the sum of demands is larger than 100 points, both players get nothing.

The Stag Hunt oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant. Each pair will go for a hunt together. They have the choice of hunting a stag or a hare. If a player chooses to hunt a stag, he can only succeed with the cooperation of the other participant. Players can get a hare by themselves, but a hare is worth less than a stag.

| Player A / Player B | Stag | Hare |

|---|---|---|

| Stag | 200 , 200 | 0 , 100 |

| Hare | 100 , 0 | 100 , 100 |

Customizable Simultaneous Game (2 to 4 actions for each player) oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant, and play up to 10 rounds of a simultaneous game.

The instructor selects the payoffs when creating the game, along with the number of actions for each player (2 to 4)

| Player 1 / Player 2 | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| A | x , x' | y , y' |

| B | z , z' | t , t' |

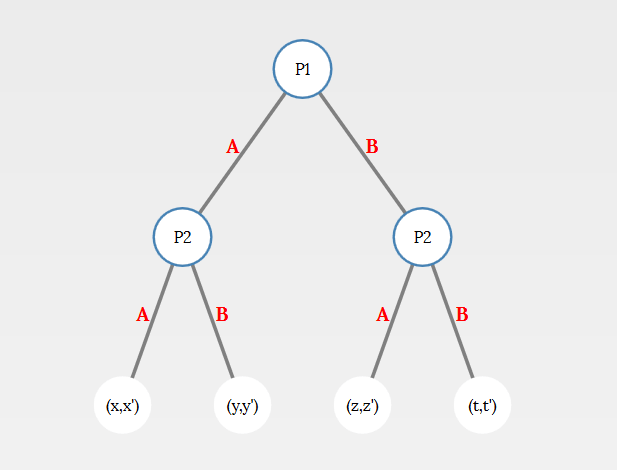

Customizable 2x2 Sequential Game oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously paired with another participant, and play up to 10 rounds of a sequential game. The instructor selects the payoffs when creating the game.

Common Value Auction oTree

Players must bid for an item that is being auctioned. Prior to bidding, each player will be given an estimate of the actual value of the item. The estimates may be different between players. The actual value of the item, which is common to all players, will be revealed after the bidding has taken place.

Vickrey Auction oTree

Players are randomly and anonymously matched with another 2 participants in an auction. Each of them is given 100 points to start.

The Market for Lemons Game oTree

In this game, players will be grouped randomly and anonymously with another 2 participants (depending on your choice when you create the game, groups will change each round or stay the same). One of them will be randomly assigned to be the buyer and the other 2 will be the sellers (players will keep this role until the end of the game). Sellers and the buyer can trade for 3 periods.

"Design a Contract: A Simple Principal-Agent Problem as a Classroom Experiment" (S. Gächter & M. Königstein) oTree

Players are owners of a firm but lack some expertise to run it and therefore decide to hire experts. They must offer them a contract, consisting of a fixed payment and a proportion of the firm's profit. The experts must then decide whether or not to accept the contract, and if they accept, how much (costly) work effort to make (which determines the total earnings of the firm).

Contracting under Incomplete Information and Social Preferences (E. Hoppe and P. Schmitz) oTree

"We consider a principal who can make a wage offer to an agent for the production of a good. The agent's production costs can be either low or high with equal probability. When the agent accepts the offer, he has to incur the production costs and the principal obtains a return. We consider a setting where the principal's return is larger than the production costs in both states of nature. Hence, ex post efficiency is achieved if the agent accepts the wage offer regardless of the state of nature.

The Bubble Game (S. Moinas & S. Pouget) Top 10! oTree

This game about speculative bubbles "is useful to discuss about market efficiency and trading strategies in a financial economics course, and about behavioral aspects in a game theory course, at all levels".

"Students sequentially trade an asset which is publicly known to have a fundamental value of zero. If there is no cap on asset prices, speculative bubbles can arise at the Nash equilibrium because no trader is ever sure to be last in the market sequence. Otherwise, the Nash equilibrium involves no trade. Bubbles usually occur with or without a cap on prices. Traders who are less likely to be last and have less steps of reasoning to perform to reach equilibrium are in general more likely to speculate."

("The bubble game: A classroom experiment," Sophie Moinas and Sébastien Pouget, Southern Economic Journal, 2016, vol. 82(4), pages 1402-1412). For advanced students, there exists a very interesting theoretical and experimental extension of this paper: "Learning in Speculative Bubbles: An Experiment" by Hong, Moinas and Pouget.

Note that a single simulation, vs robots, can also be found in the "1-player" section.

Asymmetric Information Trading Game (B. Biais, D. Hilton, K. Mazurier & S. Pouget) oTree

"... directly inspired by Plott and Sunder (1988). The value of an asset can be high (490), medium (240), or low (50). The traders observe different private signals. For example when the value of the asset is high, half the participants are privately informed that it is not low, while the others learn privately that it not medium.

Traders can place limit and market orders in a call auction and an open outcry continuous market. There is a strong winner’s curse risk in this trading game..."

("Judgemental Overconfidence, Self-Monitoring, and Trading Performance in an Experimental Financial Market," Bruno Biais, Denis Hilton, Karine Mazurier and Sébastien Pouget, 2005, Review of Economic Studies 72, 287–312.)

A Classroom Investment Coordination Experiment. (D.Hazlett) oTree

Players represent firms that make investment decisions. When they expect a recession, their resulting low levels of investment actually cause a recession. Likewise, if they expect an expansion, their resulting high levels of investment can cause an expansion.

"This experiment helps students understand theories that posit coordination failure as the cause of economic fluctuations."

("A Classroom Investment Coordination Experiment", Denise Hazlett, IREE 2007, Volume 6, Issue 1, pp. 63-76, with support from the NSF)

A Classroom Inflation Uncertainty Experiment (D.Hazlett) oTree

"This classroom experiment uses a double oral auction credit market to demonstrate how inflation uncertainty causes a wealth transfer between borrowers and lenders.

The experiment also shows the social cost of inflation uncertainty when borrowers and lenders cannot agree on a nominal interest rate that compensates each for their risk. In this case, the credit market fails to allocate funds to the highest-valued investment projects.

The experiment provides hands-on experience with the effects of anticipated and unanticipated inflation, giving students a common background for a discussion of the economic costs of inflation. It can be used in principles, intermediate macroeconomics,money and banking, or financial economics courses, with 8–60 students..."

("A Classroom Inflation Uncertainty Experiment", by Denise Hazlett, International Review of Economics Education 2008)

For any question or suggestion,